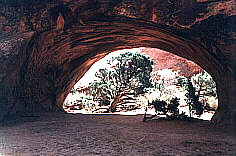

Private Arch.

Here is the story of how arches form, courtesy of the NPS.

The park lies atop an underground salt bed, which is basically responsible for the arches and spires, balanced rocks,

sandstone fins, and eroded monoliths that make the area a sightseer's mecca. Thousands of feet thick in places, this salt bed was deposited across the Colorado Plateau some 300 million years ago when a sea flowed into the region and eventually evaporated. Over millions of years, the salt bed was covered with residue from floods and winds and the oceans that came and went at intervals. Much of this debris was compressed into rock. At one time this overlying layer of rock may have been more than a mile thick.

Salt under pressure is unstable, and the salt bed below Arches was no match for the weight of this thick cover of rock. Under such pressure, the salt layer shifted, buckled, liquified, and repositioned itself,

thrusting the rock layers upward into domes. Whole sections dropped into the cavities.

Faults deep in the Earth contributed to the instability on the surface. The result of one such 2,500-foot displacement, the Moab Fault, is seen from the visitor center. This movement also produced vertical cracks that later contributed to the development of arches. As this subsurface movement of salt shaped the Earth, surface erosion stripped away the younger rock layers.

Except for isolated remnants, the major formations visible in the park today are the salmon-colored Entrada Sandstone, in which most of the arches form, and the buff-colored Navajo Sandstone. These are visible in layer cake fashion throughout most of the park. Over time water seeped into the superficial cracks, joints, and folds of these layers. Ice formed in the fissures, expanding and putting pressure on surrounding rock, breaking off bits and pieces.

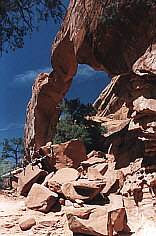

Landscape Arch (left,) and Partition Arch (center.)

Wind later cleaned out the loose particles. A series of free-standing fins remained. Wind and water attacked these fins until, in some, the cementing material gave way and chunks of rock tumbled out. Many damaged fins collapsed. Others, with the right degree of hardness and balance, survived despite their missing sections. These became the famous arches. Pothole arches form by chemical weathering as water collects in natural depressions and eventually cuts through to the layer below.

This is the geologic story of Arches -- probably. The evidence is largely circumstantial.

Here is the illustration of all this from the NPS brochure.

|